How to Write a Literature Review: A Complete Guide with Real Examples

Learn how to write a literature review step by step—with real examples, clear structure, and practical tips. A complete guide for students and researchers, plus tools to streamline your workflow.

Writing a literature review is one of the most challenging—and most misunderstood—parts of academic writing.

Many students assume it’s simply a summary of existing papers. In reality, a strong literature review is an argument: it shows how existing research fits together, where it agrees or conflicts, and why your own research question matters.

This guide walks you through what a literature review is, why it’s important, the main organizational types, and a step-by-step process you can follow, with real examples and practical tips. You’ll also see how AI tools like Kuse can help you manage sources, structure ideas, and draft more effectively—without replacing your academic judgment.

What Is a Literature Review?

A literature review is a critical overview of existing scholarly research related to a specific topic or research question.

Instead of presenting new data, it evaluates, synthesizes, and contextualizes what has already been published.

According to university writing guides, a literature review does three things at once:

- Summarizes relevant academic work

- Analyzes relationships, trends, and debates in the literature

- Positions your own research within that existing body of knowledge

In other words, a literature review answers the question:

“What do we already know about this topic, and what still needs to be explored?”

What Is the Purpose of a Literature Review?

A literature review is not a formality—it plays a strategic role in academic research and writing.

First, it establishes credibility. Demonstrating familiarity with key theories, authors, and studies shows that your work is grounded in existing scholarship.

Second, it clarifies the research landscape. By grouping and comparing studies, you reveal dominant perspectives, recurring findings, and unresolved debates.

Third, it justifies your research question. A good literature review makes clear why your research is necessary—by identifying gaps, limitations, or inconsistencies in prior work.

Finally, it guides methodology and framing. Understanding how others approached similar questions helps you refine your own research design and conceptual framework.

Three Common Ways to Organize a Literature Review

There is no single “correct” way to organize a literature review. The structure you choose should reflect both the nature of your research question and the characteristics of the existing literature. In practice, most high-quality literature reviews rely on one dominant organizational logic, sometimes combined with elements of others.

Thematic Organization

Thematic organization is the most widely used structure in contemporary academic writing, particularly in the social sciences, education, and interdisciplinary research. Instead of discussing studies one by one, this approach groups research according to shared concepts, arguments, or analytical lenses.

In a thematic literature review, individual studies are not treated as isolated units. Instead, they are positioned within broader conversations—such as competing theories, recurring findings, or contrasting interpretations. This allows the writer to move beyond description and toward synthesis, showing how multiple sources collectively contribute to understanding a topic.

For example, a iterature review on AI in education might be organized around themes such as personalization, assessment practices, accessibility, and ethical concerns. Within each theme, the reviewer compares how different studies approach the same issue, where they converge, and where tensions or contradictions remain. This structure is especially effective when the goal is to identify research gaps or conceptual disagreements.

Chronological Organization

A chronological organization arranges the literature according to publication date, emphasizing how research on a topic has developed over time. This approach is particularly useful when a field has undergone significant theoretical shifts, technological changes, or methodological evolution.

Rather than merely listing studies in sequence, a strong chronological review highlights progression. Early studies may introduce foundational theories or exploratory findings, while later research refines, challenges, or extends those ideas. The reviewer’s task is to explain why these changes occurred—whether due to new data, improved methods, or broader shifts in the field.

Chronological reviews are common in historical analyses, policy research, and emerging fields where understanding intellectual evolution is essential. However, they are less effective when used alone in mature fields with large volumes of overlapping research, as they can risk becoming descriptive rather than analytical.

Methodological Organization

A methodological organization groups studies based on how the research was conducted rather than what conclusions were reached. Studies may be categorized by qualitative versus quantitative methods, experimental versus observational designs, or data sources such as surveys, interviews, or archival records.

This approach is especially valuable when methodological choices strongly influence findings or when debates in the field center on research design rather than theory. By organizing the literature this way, the reviewer can assess how different methods shape results, identify systematic biases, and highlight underexplored approaches.

Methodological organization is often combined with thematic structure in advanced literature reviews. For example, themes may form the primary sections, while methodological differences are discussed within each theme to evaluate the robustness and limitations of existing evidence.

Step-by-Step: How to Write a Literature Review

Writing a literature review is an iterative, analytical process rather than a linear checklist. Each step informs the next, and revisiting earlier stages is both normal and necessary.

Step 1: Conduct a Strategic Literature Search

The first step is to identify relevant academic sources systematically. This involves more than typing a keyword into a search engine. Effective searches combine keywords, synonyms, subject headings, and citation tracking across multiple academic databases.

At this stage, breadth matters more than precision. The goal is to map the landscape of the research field—identifying influential authors, frequently cited works, and dominant journals. Keeping detailed notes during this phase will save time later, especially when narrowing the scope.

Step 2: Screen and Evaluate Sources Critically

Once an initial pool of sources is collected, each item must be evaluated for relevance and quality. This screening process typically involves reading abstracts first, followed by selective full-text review.

Key evaluation criteria include theoretical relevance, methodological rigor, publication credibility, and alignment with your research question. Not every source needs to be included; in fact, a strong literature review is defined as much by what it excludes as by what it includes.

This step transforms an unmanageable collection of papers into a focused, defensible body of literature.

Step 3: Move from Summary to Synthesis and Evaluation

Many literature reviews fail because they stop at summary. Synthesis requires comparing studies, identifying patterns, and interpreting relationships across findings.

At this stage, you should be asking questions such as:

How do different authors conceptualize the same phenomenon?

Where do findings align or diverge?

What assumptions underlie different approaches?

What methodological or theoretical gaps remain?

Evaluation adds another layer by assessing the strengths, limitations, and implications of existing research rather than treating all studies as equally authoritative.

Step 4: Develop a Coherent Outline

Before drafting, construct a detailed outline that reflects your chosen organizational strategy. A well-designed outline ensures logical flow and prevents redundancy.

The outline should clearly indicate how each section contributes to answering the overarching research question. At this stage, it is often helpful to write short analytical notes under each heading to clarify the argument before expanding into full paragraphs.

Step 5: Write and Integrate the Core Sections

The writing phase involves weaving sources into a coherent narrative rather than presenting them sequentially. Citations should support your analysis, not dominate it.

Strong literature reviews maintain a balance between reporting previous research and advancing the reviewer’s own analytical perspective. Transitions between sections should highlight conceptual connections, reinforcing the overall argument of the review.

Step 6: Citation and Formatting Practices

Citation styles do more than standardize appearance—they shape how arguments are presented and interpreted.

APA Style is commonly used in education, psychology, and social sciences. It emphasizes publication dates, reflecting the importance of recent research. APA requires precise in-text citations, a standardized reference list, and careful formatting of headings, tables, and figures.

MLA Style, often used in the humanities, focuses more on authorship than chronology. In-text citations are concise, and the Works Cited page follows a different logic from APA. MLA is typically preferred for literature, cultural studies, and theoretical analysis.

Chicago Style is widely used in history and interdisciplinary research. It allows for both author–date citations and footnote-based systems, making it flexible for complex source commentary and archival work.

Regardless of style, consistency is essential. Formatting errors can undermine credibility even when the analysis is strong. Tracking citations throughout the writing process—not at the end—reduces errors and stress.

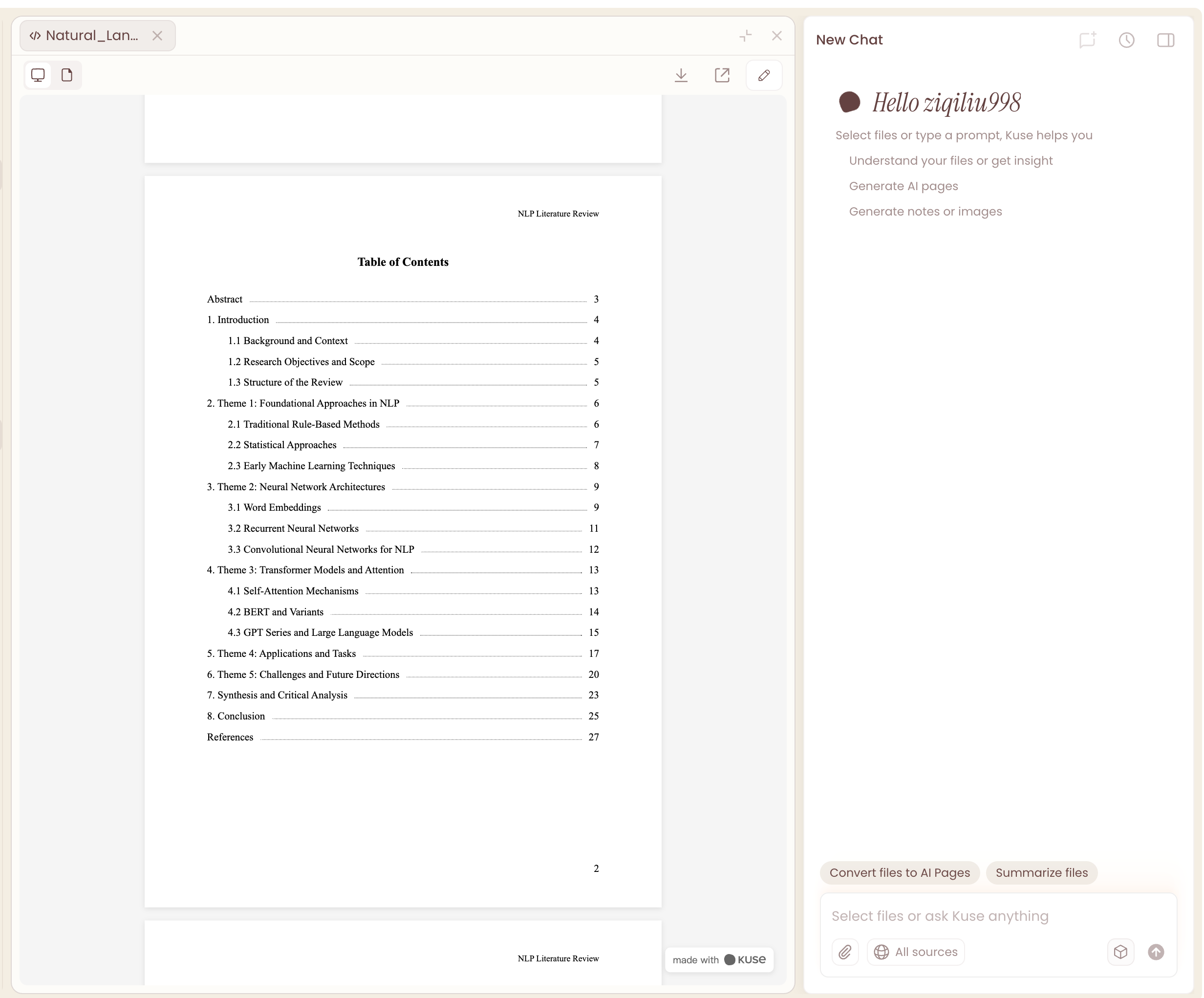

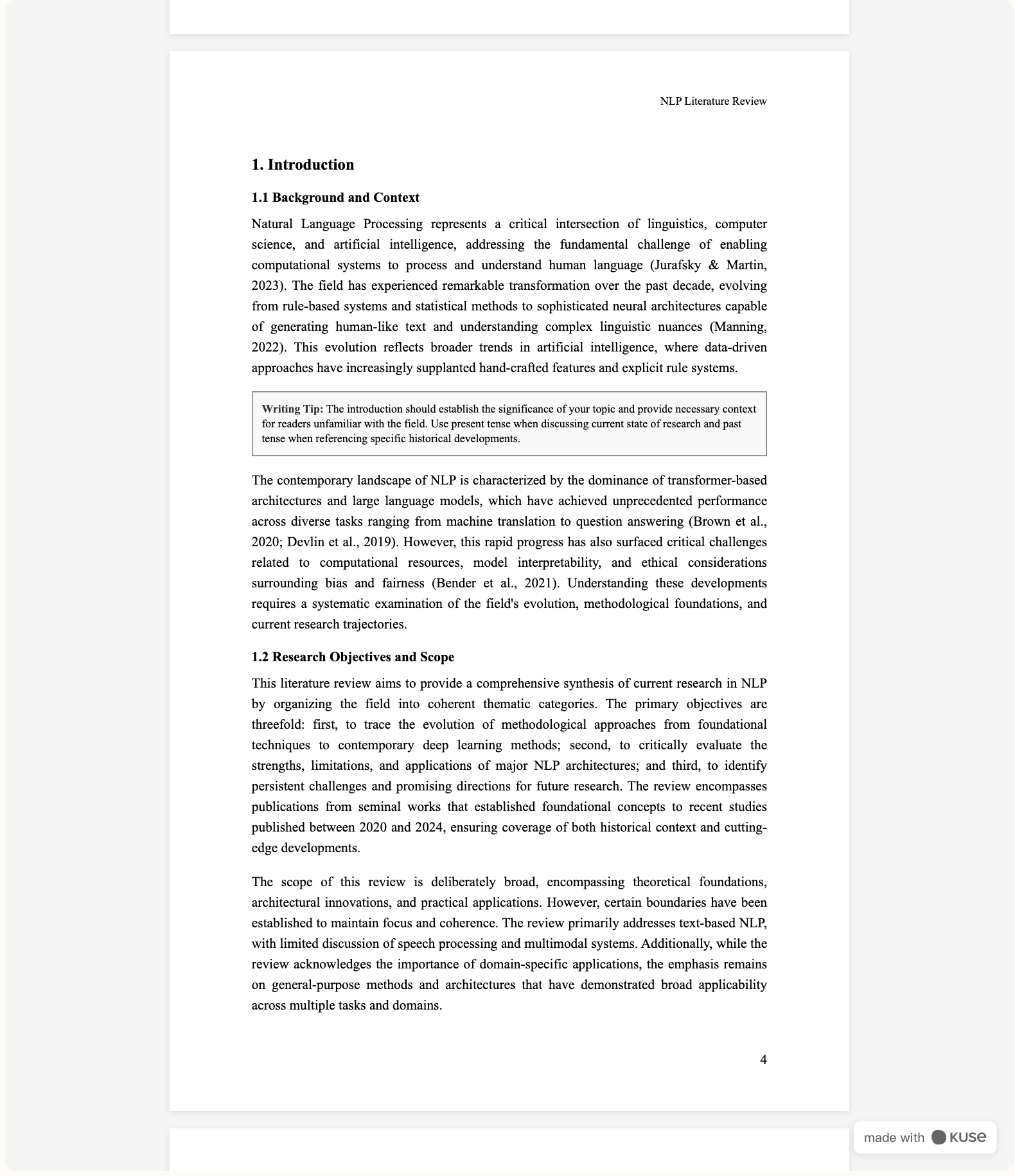

Using Kuse to Support Literature Review Writing

Kuse is particularly effective for literature reviews because it maintains contextual continuity across sources, drafts, and revisions.

A typical workflow looks like this:

First, upload all relevant materials—PDFs, annotations, lecture notes, and early drafts—into a single workspace. Kuse treats these as a connected knowledge base rather than isolated files.

Next, generate structured summaries of individual papers, focusing on research questions, methods, findings, and limitations. This creates a consistent reference layer across sources.

Then, move into synthesis by prompting Kuse to compare studies thematically, identify recurring arguments, or surface contradictions and gaps. These outputs are not final text, but analytical scaffolding for your own writing.

Once a draft exists, Kuse can help reorganize and refine structure. Example prompts include:

“Analyze the literature review and reorganize it into a professional academic structure with these sections: Introduction, Thematic Analysis, Research Gaps, and Conclusion.”

“Compare these studies and identify points of agreement, disagreement, and methodological limitations.”

“Rewrite this paragraph to improve academic tone while preserving analytical content.”

Finally, Kuse allows you to iteratively edit, restructure, and refine the review within the same environment—reducing fragmentation and helping you maintain a clear argumentative thread from start to finish.

Final Thought

Writing a literature review is less about summarizing what others have said and more about making sense of a conversation that already exists.

When done well, a literature review:

- Clarifies what is known

- Reveals what is missing

- Creates space for your own contribution

With a clear process—and the right tools—you can move from information overload to a structured, compelling review that strengthens your entire research project.