PRD Templates: Ultimate Guide and Free Examples

Free PRD templates: learn what to include, how to write a great Product Requirements Document, and get free PRD examples—plus faster ways to generate PRDs with AI.

A great product rarely fails because of engineering skill or design talent. More often, it fails because the team didn’t share the same understanding of what they were building—and why.

That’s exactly the problem a PRD template is designed to solve.

A well-written Product Requirements Document (PRD) aligns product managers, designers, engineers, and stakeholders around a single source of truth. It translates ideas into execution, strategy into scope, and user needs into concrete requirements. This guide explains what a PRD is, why it matters, what to include, and how to build one efficiently—plus real examples and modern ways to automate PRDs with tools like Kuse.

What Is a PRD?

A Product Requirements Document (PRD) is a structured document that defines what a product or feature should do, who it is for, and how success will be measured. It serves as the bridge between product strategy and product execution.

Unlike design specs or technical documentation, a PRD focuses on outcomes, constraints, and user value, not implementation details. A strong PRD answers questions like:

- What problem are we solving?

- Who is this for, and why now?

- What does success look like?

- What are we explicitly not building?

PRDs are commonly used for:

- New product features

- Major enhancements

- Platform changes

- Internal tools

- MVP and beta launches

Why a PRD Template Is Important

Using a PRD template isn’t about bureaucracy—it’s about reducing ambiguity at scale.

It aligns cross-functional teams early

Engineering, design, marketing, and leadership often approach a product from different mental models. A shared PRD template forces alignment before work begins, preventing late-stage surprises and rework.

It preserves product context over time

Teams change, priorities shift, and timelines extend. A PRD captures the original intent, constraints, and assumptions so decisions remain traceable even months later.

It improves execution quality

Clear requirements reduce guesswork. Engineers can focus on building the right solution instead of interpreting vague goals, while designers understand which trade-offs matter most.

It accelerates decision-making

Well-structured PRDs clarify what’s in scope, what’s out of scope, and which metrics matter—making prioritization and trade-off decisions faster and more grounded.

What to Include in a PRD Template

There is no single “perfect” PRD, but effective templates consistently include the following sections.

1. Overview and Context

This section sets the stage.

Background and problem statement

Why this initiative matters now

Link to broader product or business goals

The goal is to answer why this exists before diving into details.

2. Goals and Success Metrics

Define what success looks like in measurable terms.

Primary objectives (user or business outcomes)

Key metrics or KPIs

How success will be evaluated post-launch

Avoid vague goals like “improve engagement.” Be specific.

3. User Personas and Use Cases

Describe who the product is for and how they will use it.

Target user personas

Core user journeys or scenarios

Pain points being addressed

This ensures requirements stay grounded in real user needs.

4. Functional Requirements

This is the heart of the PRD.

What the product must do

Feature descriptions written from the user’s perspective

Acceptance criteria or expected behavior

Well-written requirements describe what should happen, not how it should be built.

5. Non-Functional Requirements

These define quality constraints.

Performance expectations

Security or compliance needs

Accessibility considerations

Reliability or scalability requirements

These often differentiate a prototype from a production-ready product.

6. Scope and Out-of-Scope

Explicitly define boundaries.

What is included in this release

What is intentionally excluded

Known trade-offs

This prevents scope creep and misaligned expectations.

7. Dependencies, Risks, and Assumptions

Surface uncertainty early.

Technical or organizational dependencies

Known risks

Assumptions that could change

This helps teams plan mitigation strategies instead of reacting later.

8. Open Questions and Future Considerations

Capture unresolved items and future ideas without blocking progress.

Questions to be answered later

Potential extensions or follow-ups

How to Build a PRD (Step by Step)

Building a strong PRD is less about filling in a template and more about shaping shared understanding. The process works best when it moves from context → clarity → constraint → commitment.

The first step is context gathering. Before writing a single requirement, product managers need to immerse themselves in the problem space. This includes reviewing user research, analytics, support tickets, stakeholder notes, competitive insights, and relevant strategic documents. The goal at this stage is not to decide what to build, but to understand why the problem exists and why it matters now. PRDs that skip this step often become feature lists rather than problem-solving tools.

Once context is clear, the next step is problem definition and goal setting. A well-written PRD starts with a precise problem statement that focuses on user pain or unmet needs, not proposed solutions. This is followed by clearly articulated goals that translate strategy into measurable outcomes. These goals act as a filter for everything that comes later—if a requirement does not support a stated goal, it likely does not belong in the PRD.

With goals in place, teams can move into requirement articulation. This is where the PRD begins to take shape. Effective requirements describe user-facing behavior and expected outcomes, rather than internal implementation details. Each requirement should be understandable to non-technical stakeholders while still being precise enough for engineering teams to estimate and build against. At this stage, clarity matters more than completeness; ambiguous requirements create downstream friction.

After requirements are drafted, scope definition and constraint setting become critical. Explicitly documenting what is out of scope helps prevent feature creep and protects delivery timelines. This is also where non-functional requirements—such as performance, accessibility, security, or compliance—should be clarified, ensuring quality expectations are shared early rather than enforced late.

Finally, a PRD becomes truly effective through collaborative review and iteration. Sharing early drafts with design, engineering, and key stakeholders allows teams to surface feasibility concerns, identify missing assumptions, and align on trade-offs before development begins. A PRD should be treated as a living document—refined as new insights emerge, not frozen once approved.

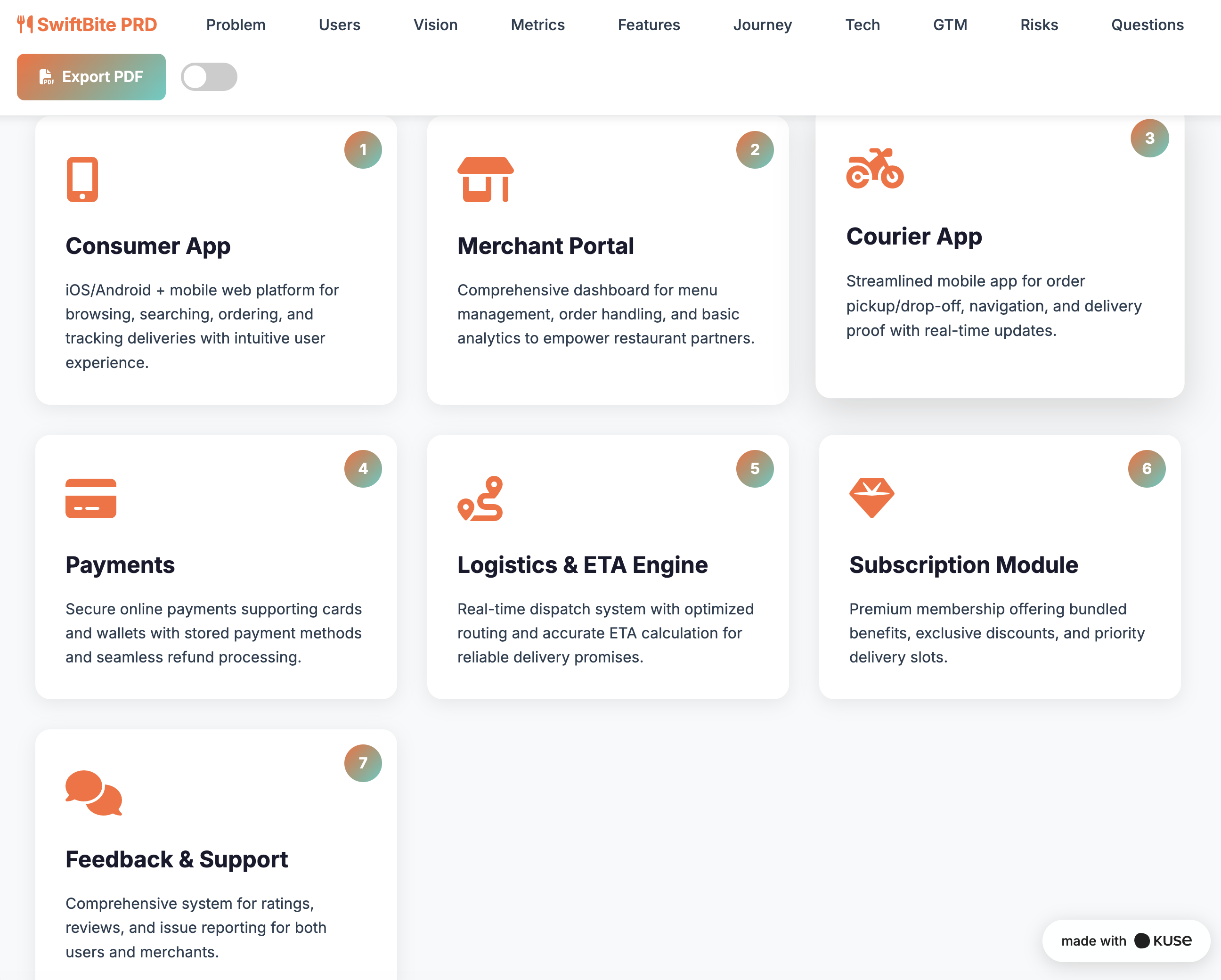

PRD Template Examples

Different teams and product contexts require different PRD styles. While the core intent remains the same, the structure and emphasis of a PRD can vary significantly.

Lean PRD

A Lean PRD is designed for speed and alignment in fast-moving environments such as startups or early-stage product teams. It prioritizes problem definition, user value, and success metrics while intentionally keeping requirements lightweight. Lean PRDs work best when teams communicate frequently and can resolve ambiguity through discussion rather than documentation.

Technical PRD

A Technical PRD places greater emphasis on precision and edge cases. In addition to functional requirements, it often includes detailed constraints, dependencies, data considerations, and integration points. This format is commonly used for platform features, APIs, infrastructure projects, or products with high technical complexity, where ambiguity can lead to costly rework.

Design-Led PRD

A Design-led PRD centers the user experience. Instead of leading with features, it emphasizes user journeys, interaction principles, and experiential goals. This type of PRD is especially effective for consumer-facing products, where usability and emotional response are as important as functional correctness. Designers often play a more active role in shaping this document.

Executive PRD

An Executive or Strategic PRD is written with leadership alignment in mind. It focuses less on detailed requirements and more on business impact, strategic rationale, trade-offs, and success criteria. These PRDs are often used to secure buy-in, guide roadmap decisions, or align cross-functional leadership before deeper execution documents are created.

Modern teams frequently maintain multiple PRD views for the same initiative—each tailored to a different audience—rather than relying on a single static document.

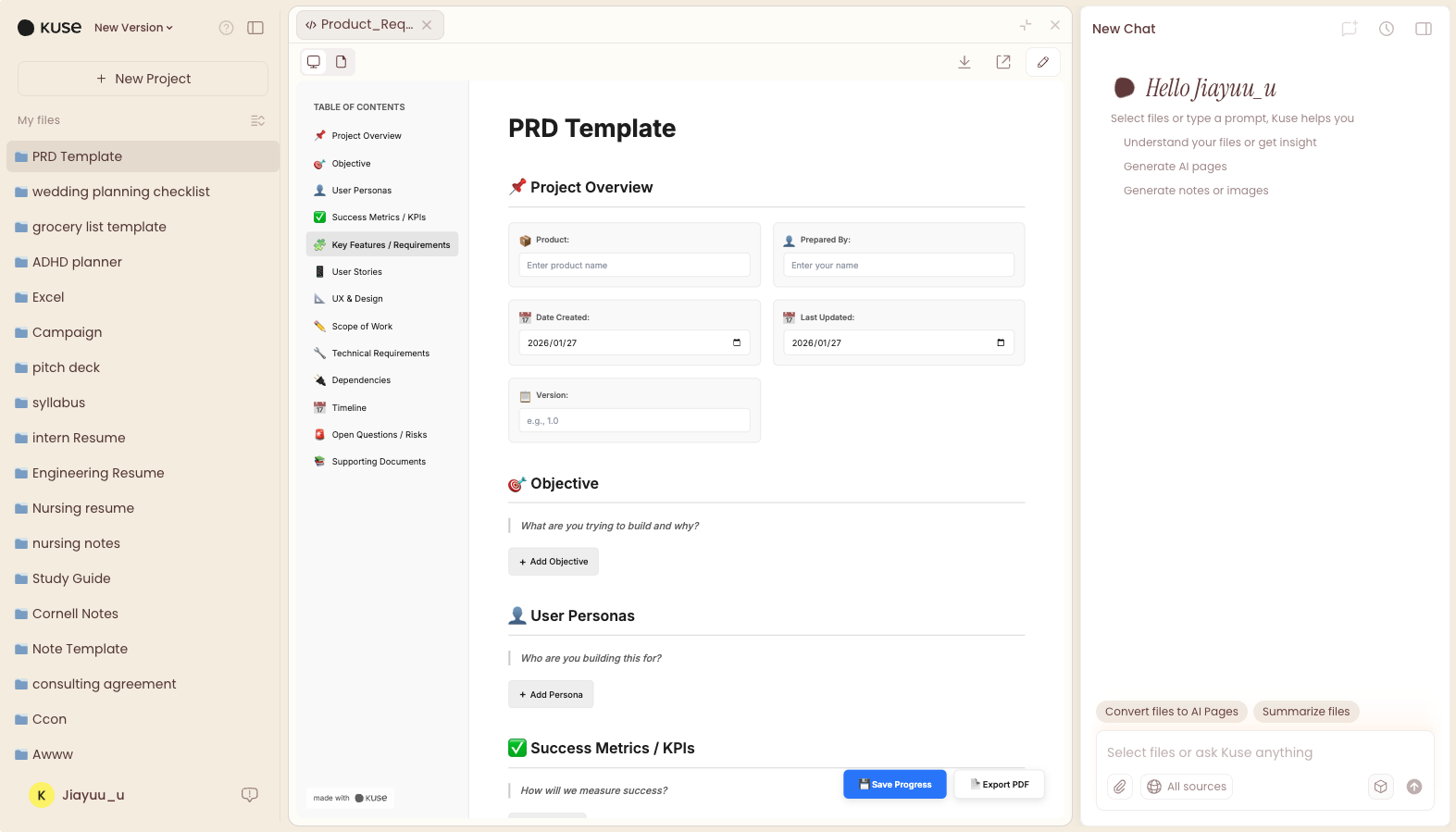

How to Quickly Generate PRD Templates with Kuse

As products grow more complex, PRDs increasingly draw from fragmented sources: user research documents, analytics dashboards, competitive analysis files, design notes, meeting transcripts, and stakeholder feedback scattered across tools.

Kuse acts as a product knowledge hub that brings these inputs together before PRD writing even begins.

Teams can upload all relevant materials—research reports, competitor analyses, previous PRDs, strategy decks, or raw notes—into a single workspace. Kuse reads and understands these materials as a connected knowledge base rather than isolated files. From there, it can generate structured PRD drafts automatically, tailored to different formats such as lean PRDs, technical PRDs, or executive summaries.

Because Kuse preserves source context, teams can iterate quickly:

- Reorganize requirements without losing rationale

- Generate multiple PRD versions for different audiences

- Update PRDs as new information arrives, without rewriting from scratch

Example prompt:

“Create a complete PRD from these inputs, including problem statement, goals, user personas, functional and non-functional requirements, risks, and success metrics. Keep the tone professional and cross-functional.”

This workflow transforms PRDs from static documents into continuously evolving knowledge artifacts that scale with the product lifecycle.

Conclusion

A PRD template is not just a document—it’s a thinking tool.

It forces clarity, alignment, and intention before code is written or designs are finalized. Teams that invest in good PRDs move faster, argue less, and ship better products.

With modern tools like Kuse, PRDs no longer need to be slow, static, or painful to maintain. They can become living documents that evolve with your product and your understanding of users.